Maps and Paintings as Documentary Evidence for the Archaeologist

Blog post by intern Rachel Huston

April is Maryland Archaeology Month! While we cannot be together in person, we want to share some of the virtual projects that The Lost Towns Project has been involved with.

With our work going remote, the Lost Towns Project’s volunteers, interns, and staff have found another way to connect with the past. Recently, we were able to analyze some primary sources over a shared video call with Dr. Julia King of St. Mary’s College of Maryland. In our discussion, we talked about Maryland’s colonial history in regards especially to the Calvert family, colonial Maryland’s first ruling family. We looked at some early maps from the 17th century that documented sites of settlements, cities and plantations. The Calverts used maps to both demonstrate and legitimize their power over the colonial landscape.

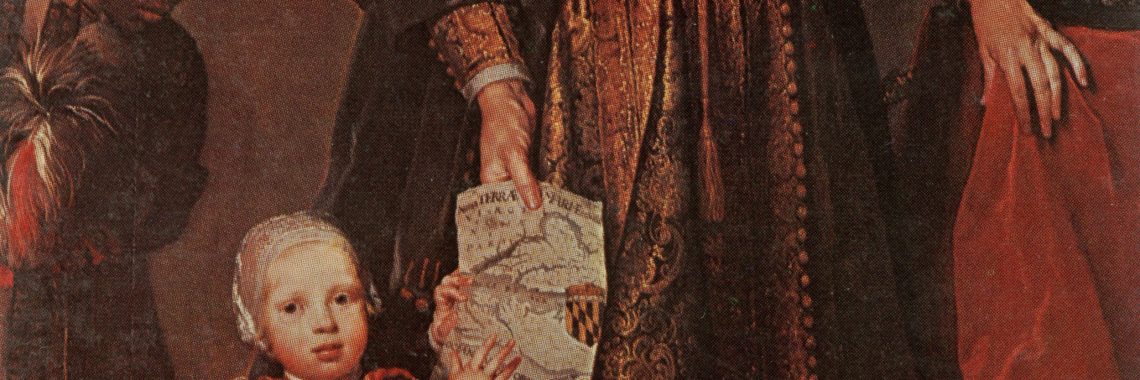

Dr. King told us to look at art as a way to understand the past and its context. Archaeologists can find out a lot about the subject of the art by seeing what it shows us. She had us take a close look at a painting called “2nd Lord Baltimore, Cecil Calvert (1606-1675)” by Gerard Soast, painted ca. 1670.

In our discussion, we looked at the noteworthy details in the painting. For example, the map that Calvert is holding looks as though it is being passed to the child, his grandson and presumptive future heir “Little Cecil”. Upon closer inspection the map depicts Maryland and Virginia, a statement of the Calvert’s power across time and space. The lush drapery and clothes further emphasize the wealth of the Calverts. An enslaved boy is depicted on the left attending to Little Cecil. We wondered about the symbolic significance of the enslaved boy, as well as what he is holding.

Alas, the future that Calvert hoped for and had depicted in this painting was not to be. Little Cecil died young, and the Catholic Calvert’s son ultimately lost the family’s power over Maryland to the Protestant Rebellion. Curiously, we saw no depictions of Catholicism in Calvert’s portrait above.

From these primary sources, archaeologists can learn about Maryland and the Chesapeake’s past. Looking at the small details in every source – whether it be paintings, maps, or pottery fragments – can help us date a site that can, in turn, be preserved. This way, we can teach the public more about local history.

To learn more, read “The Politics of Landscape in Seventeenth-Century Maryland,” by Julia A. King, Skylar A. Bauer, and Alex J. Flick, in Maryland Historical Magazine.

Rachel Huston, from Mount Airy, MD, is an intern at the Lost Towns Project and a senior at University of Maryland, College Park where she studies History and Archaeology. Her concentrations of interest include American history, local and foreign archaeological sites, and film studies.