Whitehall Overseer’s Quarter: Connecting Local African American Histories Through Archaeology on the Broadneck Peninsula

By Jennifer J. Babiarz (Anne Arundel County), C. Jane Cox (Anne Arundel County), and Lisa H. Robbins (Lost Towns Project consultant). This blog post was originally published on Our History, Our Heritage, the blog of the Maryland Historical Trust, and is cross-posted here.

In 2022, The Lost Towns Project, Inc., in collaboration with the Anne Arundel County Office of Planning and Zoning’s Cultural Resources Section, began a county-wide study—documenting and contextualizing architectural and archaeological sites representing African American households living through enslavement, resistance, and freedom during the 19th century. This project was possible thanks to an FY 2022 Historic Preservation Non-Capital Grant Award from the Maryland Historical Trust.

Products of the study include a comprehensive database of these site types in Anne Arundel County; a report providing an historical, architectural, and archaeological context for Anne Arundel County’s 19th-century African American households; and updates to, or creation of, over a dozen historic archaeological inventory forms to ensure that the state’s inventory more fully and holistically reflects the existence and importance of African American households in 19th-century Anne Arundel County.

The work undertaken at the Whitehall Overseer’s Quarters (AA-326A) was one of the more compelling sites the team studied not only because it was poorly documented in state inventory records, but also because it sparked a new level of engagement, interest, and connection with the area’s descendant community and the possibility of future partnerships and discoveries.

(*Note: This building and site is on private property, and should not be visited without the express permission of the owner(s).)

The Whitehall Overseer’s House, which stands about 40 feet west of the Overseer’s Quarters, was built in 1750 by Governor Horatio Sharpe as a one-and-a-half story frame, whitewashed house with an attached kitchen. After Sharpe’s death in 1790, Whitehall and its associated properties were willed to John Ridout, and the Whitehall Overseer’s House (AA-326) remained in the Ridout family until 2022. Horatio Ridout II and his wife Jemima Duvall were the first Ridouts to live in the Overseer’s House and likely constructed the duplex quarter for enslaved families.

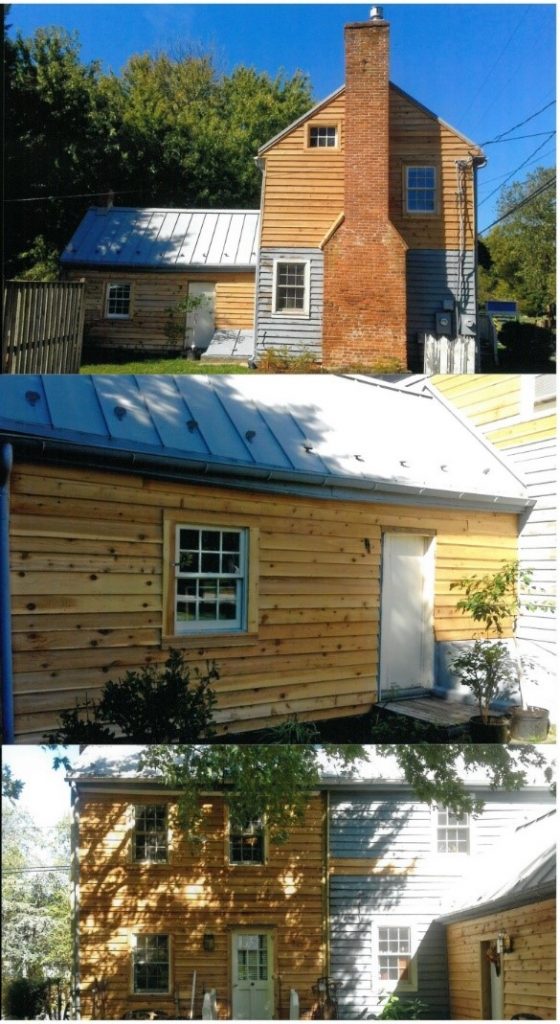

The Whitehall Overseer’s Quarters is a 1½-story log structure that rests on a roughly coursed, cut stone foundation. Its style is referred to as a double-pen saddlebag, or duplex, and consists of two independent dwellings under one roof, which were separated by a central chimney with a partition wall and likely would have housed two families. This is a common vernacular architectural form in the mid-Atlantic and the South, though this is the only surviving double-pen log quarters in Anne Arundel County and one of only a few surviving double-pen log quarters in Maryland.

Surviving evidence indicates that the building was originally constructed as one story with an accessible attic/loft, arranged in two bays (each about 14’x12’), with doorways in each corner of the façade. Based on the evidence of the surviving fasteners and finishes, the building likely was constructed between 1840-1860. Remnants of whitewash survive on surfaces throughout the interior of the building, including both logs that were added to create the half-story and logs forming the walls below. The exposed end grain of the logs forming the dovetail corner notches is remarkably unweathered, suggesting that the building may always have been enclosed with siding.

In the 1840 Census, Horatio S. Ridout II is documented as enslaving 24 individuals; by the 1850 Census the number of individuals he enslaved was 13, and in 1860 the count had dropped to nine.

There is only one recorded manumission by Horatio Ridout II: a man named John Wright in March of 1864 based on his service in the 30th Regiment of the US Colored Troops during the Civil War. Records referred to as the “Slave Statistics,” are particularly important due to their recordation of the full given name and surname of those persons who had been enslaved until the enactment of the Constitution, as well as their age, physical condition, and term of service. In reference to Horatio Ridout II, the statistics are as follows:

John Wright, 35, Male, Good, For Life, Enlisted in US services

Thomas Kemble, 34, Male, Good, For Life

Benjamin Simpson, 22, Male, Good, For Life

Gilbert Calvert, 16, Male, 16, Good, For Life

Moses Bullen, 16, Male, Good, For Life

May Smith, 30, Female, Good, 8 Years to Serve

Hester A. Simpson, 7, Female, Good, 28 Years to Serve

Isaac Smith, 3, Male, Good, 32 Years to Serve

Benjamin and Nellie Ross were interviewed by George McDaniel about the log house they moved into in the 1880s in Charles County, Maryland:

“Everybody pretty much lived in log houses back then. There were very few frame houses, and let me tell you, White and colored lived in log houses.”(McDaniel 1982:139)

The roofs of frame and log structures were typically covered with shingles, clapboards/planks, or thatch (made from grass and possibly straw in Southern Maryland).

Being located on private property, and now under the stewardship of relatively new owners, the team’s initial site visit was designed to develop a rapport with the new owners, and to gather previously unrecorded details about what we found to be a rapidly deteriorating structure. Dr. Dennis J. Pogue and MHT staff joined on some of the first visits to the site, working with the team to document and interpret this rare surviving building type. Pogue generously shared his extensive experience documenting enslaved housing for the last 15 years with the Virginia Slave Housing Project. The original MIHP form, last updated in 1976, sorely lacked architectural details, a clear statement of significance, and any consideration of possible archaeological value.

While the research design included developing measured drawings and taking photos for architectural documentation, the team also gained the trust and support of the new owners, who agreed to allow a limited Phase I archaeological survey around the Quarters. Excitement built as we began to realize the rare chance to see if there might be undisturbed and archaeologically significant deposits here, that might tell us about the families that had lived in the building during the last half of the 19th century. The team set to developing an achievable research plan for a brief one-to-two-day field session.

Having worked on other nearby sites in the area in previous months, we had also cultivated several points of contact within the local descendant communities, and knowing that they would be interested, and some had even received some limited archaeological training on other projects—we invited them to participate in the archaeological fieldwork. Our hope was that in addition to having their help with the dig, that their collective and individual memories shared through generations of their communities would also help to inform the interpretation of the site—and perhaps guide future research. In fact, we got so much more!

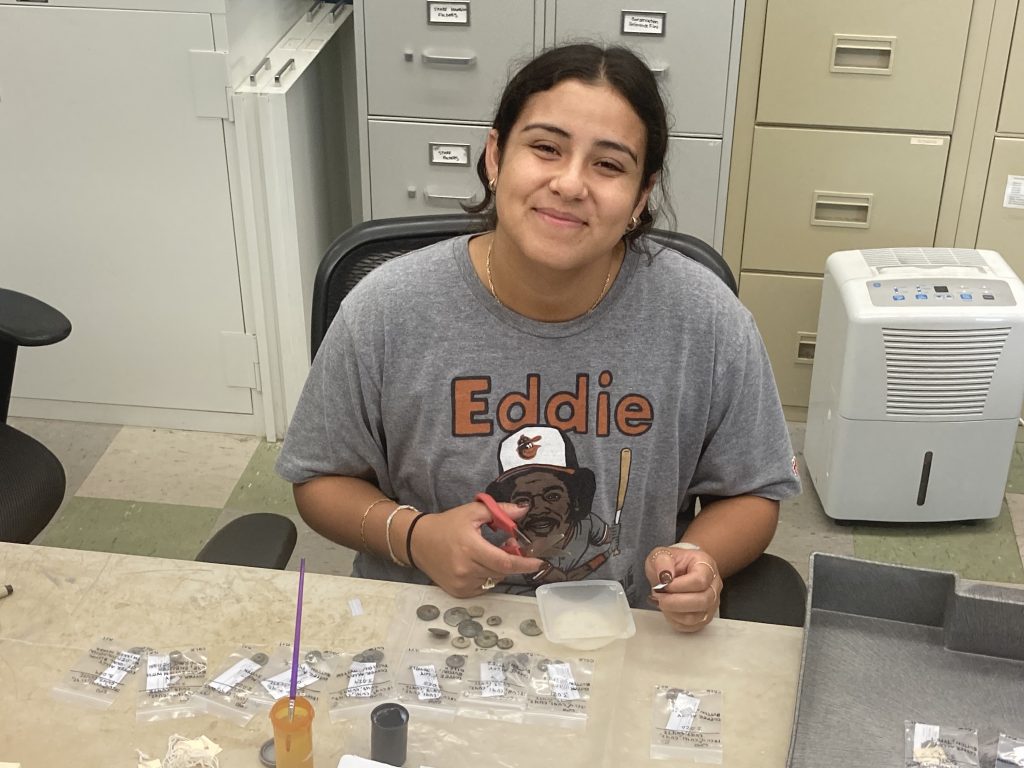

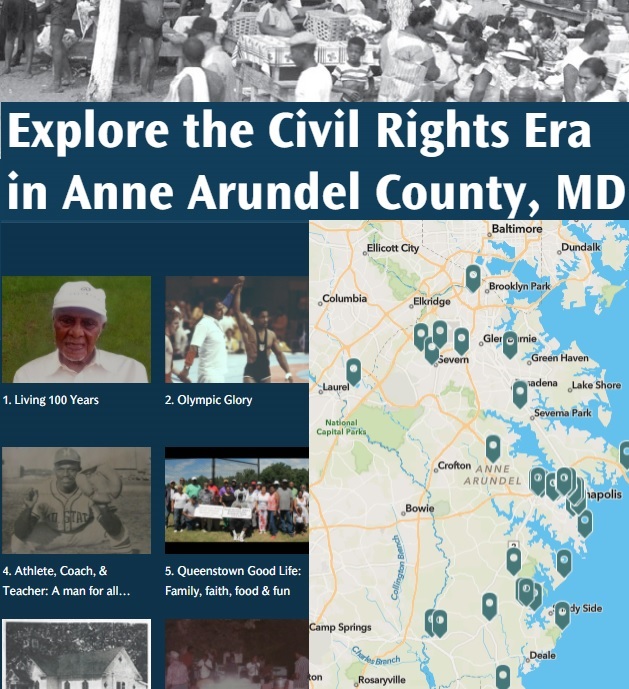

Over two days in April 2023, more than a dozen volunteers signed on to help excavate 21 close-interval shovel test pits on the lawns and terraces surrounding the Quarters. Everyone pitched in on every level of work that needed to be done, from paperwork to wielding a shovel, and their stories, laughter, and curiosity made the excavation days fly by. As volunteers from the first day shared this experience with their family and friends, the numbers swelled on the second day and cars packed in along the edge of this narrow dead-end end single-lane driveway. As they trickled in over the day, several shared that they had grown up in the area, and could connect their roots back to those who had been enslaved on the Broadneck Peninsula. Team members scrambled to monitor the digging, while also giving impromptu tours—explaining the history of the site and detailing the architecture of the building. One couldn’t help make the connection that their forefathers and mothers may well have lived in dwellings much like this one—yet most all traces of such old homes have been lost to time.

While some joined us just to see the site and spent a short time visiting, others were so intrigued that they stuck around, and jumped right in getting their hands dirty. In addition to two of our favorite volunteers April Chapman and Ann Green, we were visited by representatives from the Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture, including Director Chanel Compton and Commissioner Elinor Thompson. Well-known local historians Janice Hayes-Williams and Bernadette Pulley-Pruitt, both of whom have direct and profound connections to Broadneck, the Whitehall properties, and the Ridout family were there. Members of several organizations that have missions to help raise up and celebrate this local history also joined us, including representatives of Rev. Samuel Green, Sr. Foundation, Inc., the Annual Fathers Day Foundation such as Devon Edwards and Rev. Randy Rowe Sr, as well as representatives from the Truth, Reconciliation, and Reparations Task Force at St Margaret’s Church.

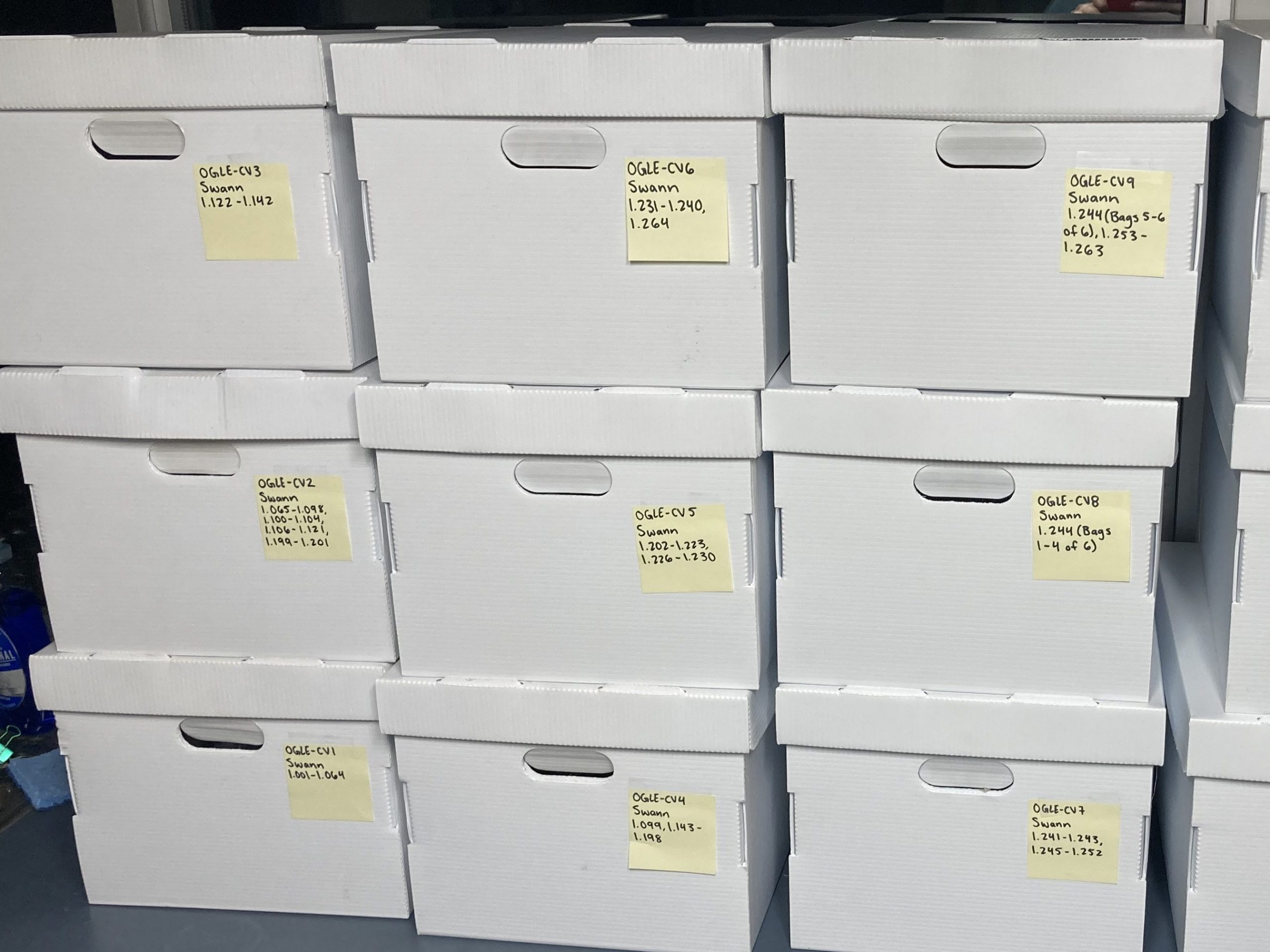

The archaeology was successful. We found evidence of historic compacted living surfaces, likely indicating swept yard spaces to the east and south of the structure, and recovered domestic and architectural artifacts that could yield new information about the historic use and layout of the space, including lead glazed redware, cut nails, and coal slag. The work clearly demonstrated that the site has research potential and further archaeological work could provide important details of everyday life for those enslaved, and later tenant families, living in this building. The archaeology however was also important to better acknowledge and appreciate such a site for state and local history, including for generations of descendants.

For the descendants of those who resisted violence and coercive control by building families, and vibrant households that have survived through generations in the same area, the chance to discover and hold everyday items that had likely been part of their everyday lives during that process was very moving. Many of the descendants that we worked with us expressed feeling closer to their ancestors than ever before; though not necessarily peaceful, it was very meaningful to them. Black spaces are being erased from the landscape at an alarming rate throughout the state and county. It is through ongoing partnership building with descendant communities and landowners that these spaces can be more fully identified and documented through the Maryland Inventory of Historic Places forms. African Americans’ crucial contributions to the economic and cultural development of Anne Arundel County should be acknowledged and celebrated through their representation in the official documentation of local and state histories.

References Cited:

ANNE ARUNDEL COUNTY COMMISSIONER OF SLAVE STATISTICS (Slave Statistics). 1867, MSA C142, pg 87, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland.

Manumission Papers, database, Legacy of Slavery in Maryland (https://slavery2.msa.maryland.gov/pages/Search.aspx: April 11, 2024), Entry for Horatio Ridout.

McDaniel, George W. 1982 Hearth and Home: Preserving a People’s Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Virginia Slave Housing, Special Projects, School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, University of Maryland, College Park (https://arch.umd.edu/research-creative-practice/special-projects/virginia-slave-housing: April 12, 2024)

US CENSUS BUREAU (Census Record, MD), Slaves 1850. Maryland State Archives, MSA SM61-156, pg 369. Annapolis, Maryland.

US CENSUS BUREAU (Census Record, MD), Slaves 1860,. Maryland State Archives, MSA SM61-226, pg 32. Annapolis, Maryland.

www.revsamuelgreensrfoundation.org/

www.annualfathersdayfoundation.com

www.africanamerican.maryland.gov/

www.st-margarets.org/truth-reconciliation-and-reparations-task-force.html