Dr. Emily Wilson: A Pioneering Country Doctor

Dr. Emily Hammond Wilson was a pioneer in the medical profession and accomplished a lot of firsts in her life, including practicing outside racial norms during the era of segregation. Over her 53 year career, she garnered a lot of respect and endearment among her peers, friends, and the local community.

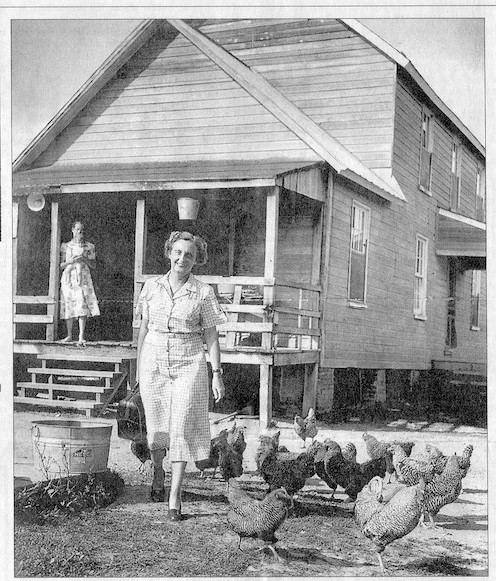

Born on July 8, 1904 in Beech Island, South Carolina, Emily graduated in 1927 from the Medical College of Georgia. She was the only woman in her class and only the second woman to graduate from the school. She would end up researching at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore before becoming the first female doctor in South Anne Arundel County. In 1929, Emily borrowed money from her uncle and set up her practice in Lothian, MD. She had to prove herself from the start, as many residents were wary of her capabilities as a female doctor. In 2004, she was quoted in The Capital as saying “One woman told me she sent for me just to see what I looked like. People weren’t real sure I knew what I was doing.” Her first office was in a summer kitchen with no water and electricity. She was very much a country doctor, making house calls by horseback or buggy when the local roads were too muddy to traverse by car. When patients did not have the cash money to pay her ($1 for office visits and $15 for at-home baby deliveries), they would often pay her with a bushel of oysters, chickens, or farm labor work.

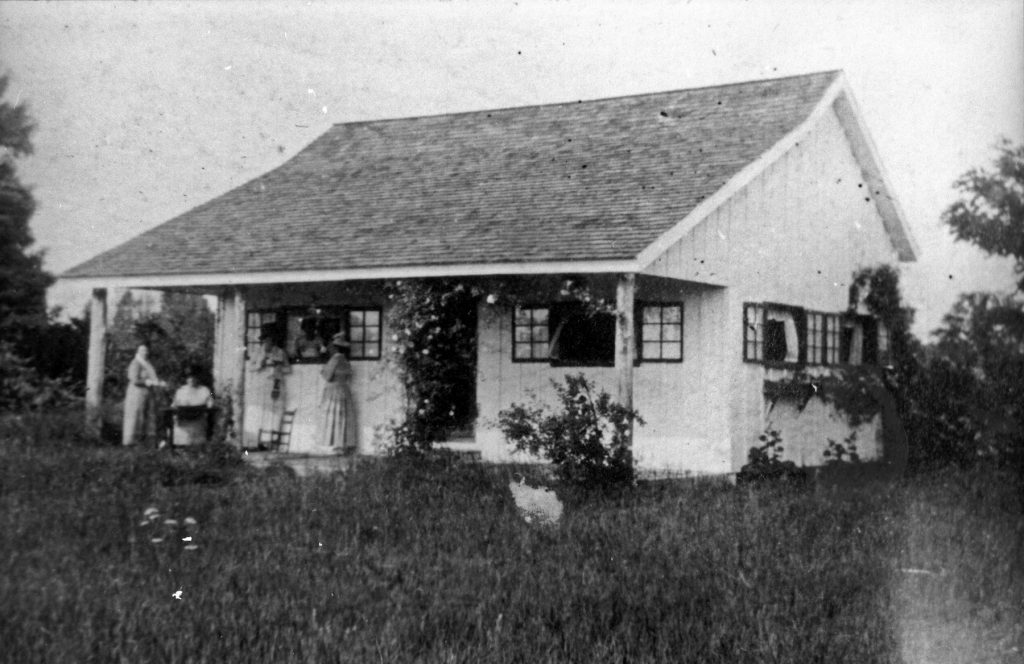

In 1932, she married her first husband, John Fletcher Wilson. Together, they purchased the historic “Obligation” property in the 1940s. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the dwelling was built in 1743 for the locally prominent Stockett family. Unfortunately, when the Wilsons purchased the property, it was in a deteriorated state, but they worked hard to restore it and it is where Dr. Wilson lived the remainder of her life. Around the same time, she moved her office to the small building at the corner of Solomon’s Island Rd and Owensville Rd (Rt. 255) which was formerly a tea house that was owned and operated by local resident, Anne Cheston. Anne was the daughter of Dr. Caspar Morris Cheston and Sally Murray Cheston and was a long time resident of Owensville. She built the tea house when the State Road was built around 1910.

In early 20th century America, tea houses were women-owned and operated businesses and became a “third place” for other women to gather and socialize. This was a huge milestone in the social and commercial history of women in this country, as most businesses and social clubs were male dominated. Many of Anne Cheston’s male forbearers, in fact, were members of the prominent Old South River Club (the longest surviving men’s club in America) that still stands today on South River Clubhouse Road. Unfortunately, the tea house was not a successful venture and closed after a few years and then became a dwelling for many years prior to it becoming the office of Dr. Wilson. The building still stands today as a commercial business.

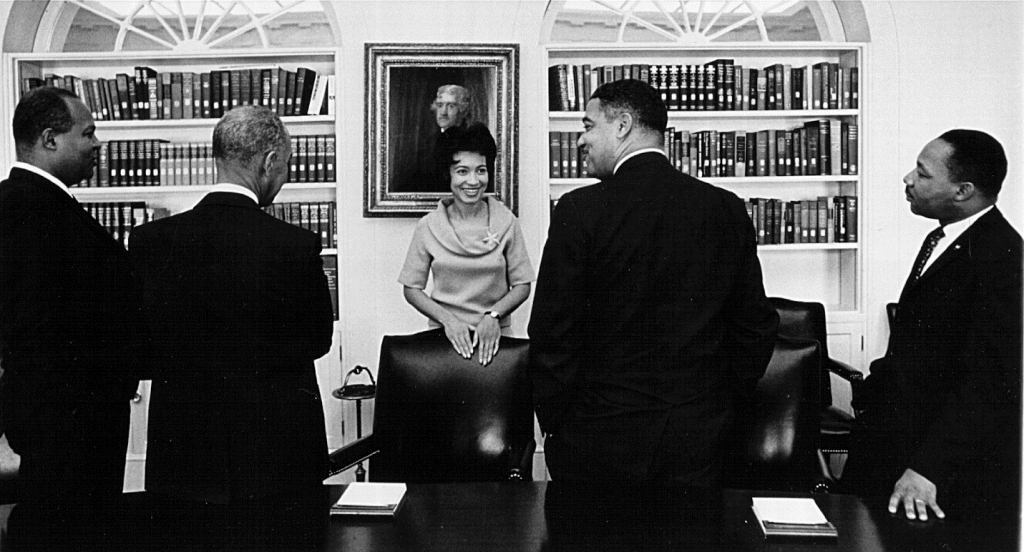

Unlike many doctors’ offices in America that were segregated, Emily Wilson did not abide by those same constraints. Her patients, both white and black, sat in the same waiting room and she showed no preference in the order that they were seen. It was always on a first-come first-served basis and depended on the seriousness of the ailment. She also made herself available to any sick person needing medical care, no matter who they were or what time of day it was. She continued her groundbreaking career by becoming the president of the Anne Arundel Medical Society in 1951 and the Chief of Staff of Anne Arundel Hospital, now Anne Arundel Medical Center. As Chief of Staff, she established clinics for pre-natal care and to treat syphilis. Dr. Wilson gave up practicing at the age of 78 and is said to have delivered over 1,000 babies during her long career. She remained living at Obligation in Harwood and was active in the community until her death on July 10, 2007 at 103 years old.

Contributed by Darian Beverungen, Historic Sites Planner, Anne Arundel County Cultural Resources Section.

References:

Magnotti, Therese. Doc: The Life of Emily Hammond Wilson. Published by the Shady Side Rural Heritage Society.

“Emily Hammond Wilson Walker MD (1994-2007).” MSA SC 3520-14731. Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series).